~ 14 min read

Recapitulating SOLID Design Principles in JavaScript

In the world of software development, the pursuit of ‘good’ design can be as elusive as it is essential. Picture this: a group of seasoned developers, each with their unique experiences and backgrounds, gathered around a conference table. They’re tasked with designing a new software system. As they engage in discussions, it becomes apparent that their definitions of a ‘good’ design are as diverse as the projects they’ve worked on.

Why such disparities in perspective? The answer lies in the rich tapestry of software domains. In one corner, there are projects where speed and prototyping are paramount – think startup environments where agility can make or break a company. In another corner, there are industries like finance and healthcare, where data security, maintainability, and reliability are non-negotiable.

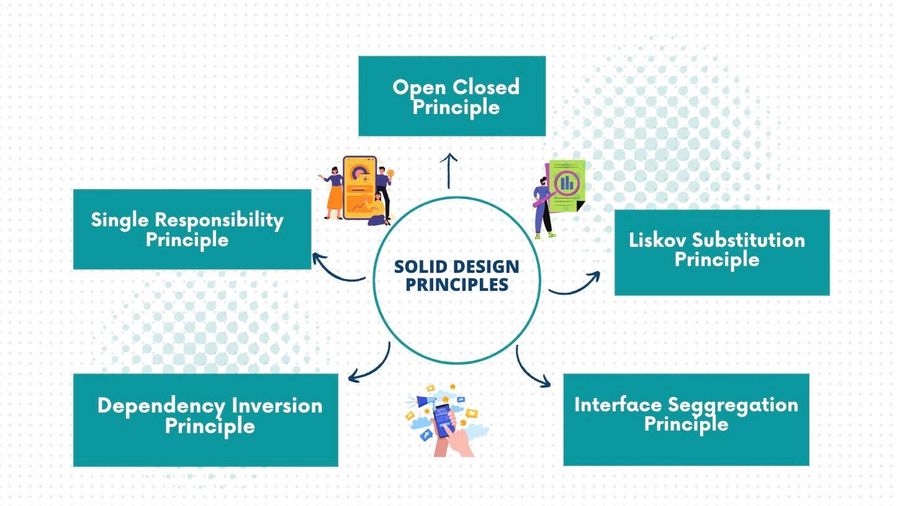

The SOLID design principles provide ideas on writing understandable, maintainable, and flexible software that does not rot with the addition of logic. The term SOLID is a mnemonic acronym for five design principles explained in an Object Oriented Setting by Robert C. Martin (a.k.a Uncle Bob).

Quoted from one of his articles:

Given some code or design that you feel bad about, you may be able to find a design principle that explains the problem and advises you about a better solution. They are common-sense disciplines that can help you stay out of trouble. They have been observed to work in many cases; but there is no proof that they always work, nor any proof that they should always be followed.

Uncle Bob adds that these principles are gathered from empirical evidence and are applicable to designing a simple module or larger architectures while developing software. In this article, We are going to discuss the SOLID principles and demonstrate examples of good and bad designs in JavaScript. The five design principles (i.e. acronym for SOLID) are:

1) Single Responsibility Principle

A class should have only one responsibility which means ‘reason to change’ or say a single role to play. The single responsibility principle states that:

If you can think of more than one motive for modifying a class or that class has to be changed for multiple actors or groups, then that class has more than one responsibility and must be decomposed.

Example

When designing a User class, we may have the temptation to store all the user-related operations in a single class that returns the name, sends an email to a user, and saves the user on the database as shown below.

class User {

name = "";

age = 0;

constructor(name, age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

getUserName() {

return this.name;

}

sendEmail() {

//logic to send email

}

saveUser() {

//logic to save user to db

}

}However, this is a bad design since any new change in the email logic or database persistence logic may affect the user class read or write operations. Therefore, it violates the SRP. Therefore, responsibility-based separation rather than keeping different functionalities together that users perform would be cleaner and loosely coupled approach i.e. EmailHandler class for sending email and the DBHandler class for persisting data.

class User {

name = "";

age = 0;

constructor(name, age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

getUserName(){

return this.name;

}

}

class EmailHandler {

email_config = "";

constructor(email_config){

this.email_config = email_config;

}

sendEmail(receiver){

// logic to send email

}

}

class DBHandler {

saveUser(){

// save user to Databaser

}

}2) Open Closed Principle

If changing one part of a program results in multiple changes in other parts, it indicates poor design and can lead to issues like fragility, inflexibility, unpredictability, and difficulty in reusing code. To avoid this, the open-closed principle suggests designing modules that remain unchanged and adding new code to expand their functionality instead of modifying existing code when requirements change.

The Open Closed principle originally devised by Bertrand Meyer in the 1980s appeared in his book Object-Oriented Software Construction. It states that:

This principle assists us in creating designs that are stable in the face of change and that will last longer. The primary mechanisms behind the Open-Closed principle are abstraction and polymorphism.

Here, the two primary attributes to keep in mind are:

-

Open for Extension This means that we can make the module behave in new and extended ways as the requirement of the application changes.

-

Closed for Modification This means that the source of such a module cannot be changed directly. No significant program can be 100% closed. Since closure cannot be complete, it must be strategic. That is, the designer must choose the kinds of changes against which to close his design. This takes a certain amount of prescience derived from experience.

The following heuristics and conventions are significant while we follow the OCP:

- Member variables of a class should be private

- No Global Variables unless the convenience offered is worth the cost

- Use run time type identifications cautiously

Also, In order to make a program more adaptable to changes, the designer must be dedicated to abstracting certain parts of it based on requirements.

Example

We will use the famous Shape class example to demonstrate OCP. A common tendency while calculating the area of multiple shapes is to create a Shape class that returns the area of the type of shape with dimensions passed.

class Shape {

type = "";

length = 0;

breadth = 0;

radius = 0;

constructor(type, length, breadth, radius) {

this.type = type;

this.length = length;

this.breadth = breadth;

this.radius = radius;

}

// Notice that this code needs to be modified to add new shape

getArea(shape) {

if (shape.type == "rectangle") {

return shape.length * shape.breadth;

} else if (shape.type == "circle") {

return (22 / 7) * shape.radius ** 2;

}

}

}

//client code

const rectangle = new Shape("rectangle", 10, 5);

rectangle.getArea();This approach is alright unless you want to add a new shape, let’s say a Triangle type. You would have to modify the original getArea function to support the logic for calculating its area. This approach makes the system vulnerable to side effects when new code is introduced and thus violates the OCP. However, by refactoring our Shape class using polymorphism we can make the code open for extension but closed for modification.

class Shape {

getArea() {

throw new Error("This method must be overridden.");

}

}

class Rectangle extends Shape {

length = 0;

breadth = 0;

constructor(l, b) {

super();

this.length = l;

this.breadth = b;

}

getArea() {

return this.length * this.breadth;

}

}

class Circle extends Shape {

radius = 0;

#PIE = 22 / 7;

constructor(r) {

super();

this.radius = r;

}

getArea() {

return this.#PIE * this.radius ** 2;

}

}

// client code

const rectangle = new Rectangle(10, 5);

rectangle.getArea();

const circle = new Circle(10);

circle.getArea();

Now, if we need to add area calculation support for Triangle, we would simply do as follows.

class Triangle extends Shape {

height = 0;

base = 0;

constructor(h, b){

super();

this.height = h;

this.base = b;

}

getArea() {

return (1 / 2) * this.height * this.base;

}

}

// client code

const triangle = new Triangle(4,5);

triangle.getArea();3) Liskov Substitution Principle

Barbara Liskov first wrote the LSP as follows - nearly 8 years ago:

What is wanted here is something like the following substitution property: If for each object o1 of type S there is an object o2 of type T such that for all programs P defined in terms of T, the behavior of P is unchanged when o1 is substituted for o2 then S is a subtype of T.

This rule can be paraphrased as:

The LSP bears a certain resemblance to Bertrand Meyer’s design by contract.

This model also suggests that when considering whether a particular design is appropriate or not, one must not simply view the solution in isolation but rather in terms of the reasonable assumptions that will be made by the users of that design.

The Open-Closed principle is at the heart of many of the claims made for Object Oriented Design. It is when this principle is in effect that applications are more maintainable, reusable, and robust.

The Liskov Substitution Principle (A.K.A Design by Contract) is an essential feature of all programs that conform to the Open-Closed principle. It is only when derived types are completely substitutable for their base types that functions that use those base types can be reused with impunity, and the derived types can be changed with impunity.

Example

Consider the following example. We have a Bird class, and what we would want is to extend this class when defining every new Bird.

class Bird {

name = ""

constructor(name){

this.name = name;

}

fly() {

throw new Error("This method must be overridden.");

}

getName(){

return this.name;

}

}

class Eagle extends Bird {

fly(){

// fly function

}

}

class Ostrich extends Bird {

//can not fly

}Here, the derived classes Eagle and Ostrich are not substitutable for their base class. Thus, it violates the LSP. Consider we have a function that takes an Array of Bird as an argument and flies them to return each bird’s flight distance.

/**

* Flies the birds and stores the flight distance of each

* @param {b} Bird[]

*/

function flyer(b) {

return b.map((bird) => bird.fly());

}Since our Ostrich bird does not implement the fly() function this implementation will fail for the derived class Ostrich but will succeed for the Eagle class.

Thus, in such a case, a nice approach would be as shown.

class Bird {

name = "";

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

getName() {

return this.name;

}

}

class FlyingBirds extends Bird {

fly() {

throw new Error("This method must be overridden.");

}

}

class Eagle extends FlyingBirds {

fly(){

// fly function

}

}

class Ostrich extends Bird {

// class body

}

//client code

/**

* Flies the birds and stores the flight distance of each

* @param {b} FlyingBirds[]

*/

function flyer(b) {

return b.map((bird) => bird.fly());

}4) Interface Segregation Principle

When clients are obligated to rely on interfaces irrelevant to their usage, they become vulnerable to alterations made to those interfaces. This unintentionally links all clients together. Put differently, if a client is reliant on a class housing interface that the client itself doesn’t utilize, but that other clients depend on, then any modifications those other clients impose on the base class will impact the first client. The interface Segregation Principle aims to minimize these associations whenever feasible, aiming to segregate interfaces when it makes sense to do so.

Example

We can use Separation through the delegation method or Separation through multiple inheritance to segregate interfaces.

Presenting this demonstration in JavaScript is slightly more challenging due to the absence of formal interfaces. Nonetheless, we can illustrate it effectively by employing the concept of composition.

Consider a Shape class with area and volume methods to calculate area and volume of the shape respectively. We have Cuboid and Circle class that extend this Shape class since both of them are shapes. Though the design looks quite obvious, it has flaws since our Circle class which is a 2D shape is forced to implement the volume method of 3D shape.

class Shape {

area() {}

volume() {}

}

class Cuboid extends Shape{

//

}

// class circle is forced to use the volume calculation functionality

// any changes on volume function might affect Circle Class which is

// undesired

class Circle extends Shape {

//

}Refactoring our code with reference to the Interface Segregation Principle we can decouple our Circle class with the volume methods logic using composition. This flaw can be handled in other languages through multiple inheritance or Adapter pattern. You can see more about this in references.

const shape = {

area: function () {

return this.l * this.b;

},

};

const threeDShape = {

volume: function () {

return this.l * this.b * this.h;

},

};

class Circle {

constructor(l, b) {

this.l = l;

this.b = b;

}

}

class Cuboid {

constructor(l, b, h) {

this.l = l;

this.b = b;

this.h = h;

}

}

Object.assign(Circle.prototype, shape);

Object.assign(Cuboid.prototype, shape, threeDShape);

const circle = new Circle(4, 3);

const cuboid = new Cuboid(4, 3, 5);

console.log(circle.area());

console.log(cuboid.volume());5) Dependency Inversion Principle

The dependency inversion principle takes into consideration the rigidity(hard to reuse), fragility(small change breaks other parts of the code), and Immobility(hard to reuse) of a bad design. The dependency inversion principle states that:

Consider the implications of high-level modules that depend upon low-level modules. It is the high-level modules that contain the identity, important policy decisions, and business models of an application. Yet, when these modules depend upon the lower level modules, then changes to the lower level modules can have direct effects on them; and can force them to change. This predicament is absurd! It is the high-level modules that ought to be forcing the low-level modules to change. When high-level modules depend upon low-level modules, it becomes very difficult to reuse those high-level modules in different contexts.

Example

Dependency Inversion can be applied wherever one class sends a message to another. For example, consider the case of the Button class sending on and off signals to the Lamp class. Button should not need to know about the concrete implementation about which device it turns on or off, it just sends its message to some ButtonClient. Devices using the button implementation (i.e. Lamp) could implement the ButtonClient. In this way, the Button and Lamp are not dependent on concrete implementations.

Or, Consider the case of a Copy Handler that reads a character from the Keyboard or any device and writes it to some other device say a Printer.

// Consider a copy program that contains

// a KeyboardReader and ConsoleWriter module

class KeyboardReader {

character = ""

read(){

console.log("Read from Keyboard", this.character)

}

}

class PrinterWriter {

write(character){

console.log("Writing to Console", character);

}

}

class DiskWriter {

write(character){

console.log("Writing to Disk", character);

}

}

const OutputDevice = {

printer: 'printer',

disk: 'disk'

};

// This copy function is dependent upon its implementation

// since adding a new type of reader or writer requires modification

// on this function, thus it violates dependency inversion

function copy(dev) {

let c;

const keyboardReader = new KeyboardReader();

const diskWriter = new DiskWriter();

const printerWriter = new PrinterWriter();

while ((c = keyboardReader.read()) !== EOF) {

if (dev === OutputDevice.printer) {

printerWriter.write(c);

} else {

diskWriter.write(c);

}

}

}

$(function main (){

copy();

})()Following the DIP principle, after abstraction on our classes we get,

// Reader class (equivalent of abstract class)

class Reader {

read() {

throw new Error("read method must be overridden");

}

}

// Writer class (equivalent of abstract class)

class Writer {

write(char) {

throw new Error("write method must be overridden");

}

}

// Concrete implementations

class KeyboardReader extends Reader {

read() {

// Implement read from keyboard

// Return character or EOF

}

}

class PrinterWriter extends Writer {

write(char) {

// Implement write to printer

}

}

class DiskWriter extends Writer {

write(char) {

// Implement write to disk

}

}

// Copy function

function copy(reader, writer) {

let c;

while ((c = reader.read()) !== EOF) {

writer.write(c);

}

}

$(function main() {

const keyboardReader = new KeyboardReader();

const printerWriter = new PrinterWriter();

copy(keyboardReader, printerWriter);

})();Tips

What’s the problem with conventions? The conventions to use something in some specific way are often violated in several parts of the application by engineers who do not understand its necessity. That is the problem with conventions, they have to be continually re-sold to each engineer. If the engineer does not agree, then the convention will be violated. And one violation ruins the whole structure.

This blog encapsulates my understanding of SOLID design principles. Would you like to explore deeper? Then, check out the references. Also, please let me know if you have any misgivings or you found any mistakes in my blog.

Thank you !! Until next time !!! 🕰️

References

https://sites.google.com/site/unclebobconsultingllc/getting-a-solid-start

https://web.archive.org/web/20150202200348/http://www.objectmentor.com/resources/articles/srp.pdf

https://web.archive.org/web/20150905081105/http://www.objectmentor.com/resources/articles/ocp.pdf

https://web.archive.org/web/20150905081111/http://www.objectmentor.com/resources/articles/lsp.pdf

https://web.archive.org/web/20150905081110/http://www.objectmentor.com/resources/articles/isp.pdf

https://web.archive.org/web/20150905081103/http://www.objectmentor.com/resources/articles/dip.pdf